ORP Versus Amperometry

- Home

- ORP Versus Amperometry

Total Residual Oxidant Measurement: ORP or Amperometry

There are two available methods for Total Residual Oxidant (TRO) measurement: Oxidation Reduction Potential (ORP) and amperometry. Until now, there have been no amperometric sensors that have been practical in a ballast water application. This paper will examine the relative benefits and limitations of both methods.

ORP measurement is the least expensive method available for water monitoring. It is primarily used in the swimming pool industry as well as some niche applications such as cyanide destruction (plating and mining industries). It is frequently used as a qualitative indicator. In commercial swimming pools, when used to control chlorine feeding equipment most operators frequently measure the chlorine level manually, often on a daily basis. The presence of high levels of organic molecules can foul the sensor within days, requiring cleaning.

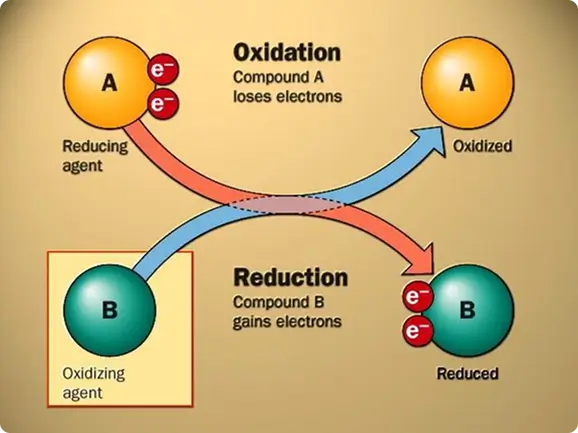

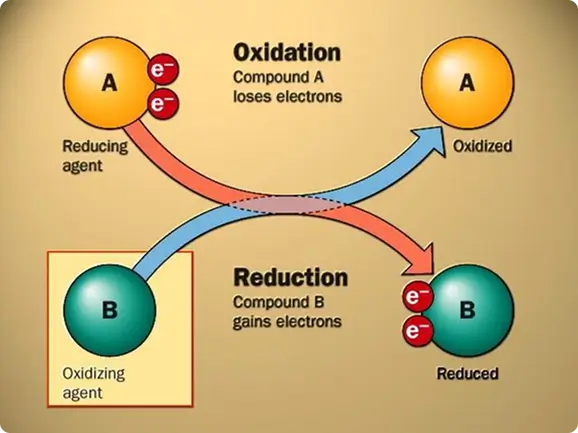

ORP stands for oxidation-reduction potential, which is a measure, in millivolts, of the tendency of a chemical substance to oxidize or reduce another chemical substance. Oxidation is the loss of electrons by an atom, molecule, or ion. The electrons lost by the atom in the reaction cannot exist in solution and have to be accepted by another substance in solution. So the complete reaction involving the oxidation will have to include another substance, which will be reduced Figure 1.

THE MEASUREMENT OF ORP

An ORP sensor consists of an ORP electrode and a reference electrode, as a Voltmeter measures the difference in potential (voltage). The principle behind the ORP measurement is the use of an inert metal electrode (platinum, sometimes gold), which, due to its low resistance, will give up electrons to an oxidant (chlorine in this case) or accept electrons from a reductant (sulfur dioxide in a dechlorination process) . The ORP electrode will continue to accept or give up electrons until it develops a potential, due to the build up charge, which is equal to the ORP of the solution. The typical accuracy of an ORP measurement is ±5 mV. This further complicated by the fact that different probes from the same manufacturer often will have a 20 to 50 mV difference in the same water sample.

An ORP sensor consists of an ORP electrode and a reference electrode, as a Voltmeter measures the difference in potential (voltage). The principle behind the ORP measurement is the use of an inert metal electrode (platinum, sometimes gold), which, due to its low resistance, will give up electrons to an oxidant (chlorine in this case) or accept electrons from a reductant (sulfur dioxide in a dechlorination process) . The ORP electrode will continue to accept or give up electrons until it develops a potential, due to the build up charge, which is equal to the ORP of the solution. The typical accuracy of an ORP measurement is ±5 mV. This further complicated by the fact that different probes from the same manufacturer often will have a 20 to 50 mV difference in the same water sample.

Note: manufactures test their sensors in Zobell Solution which contains a high level of redox couples. In this solution sensors will read very close to each other. That is not the case with real world samples in drinking water.

ORP Electrodes are Easily Poisoned

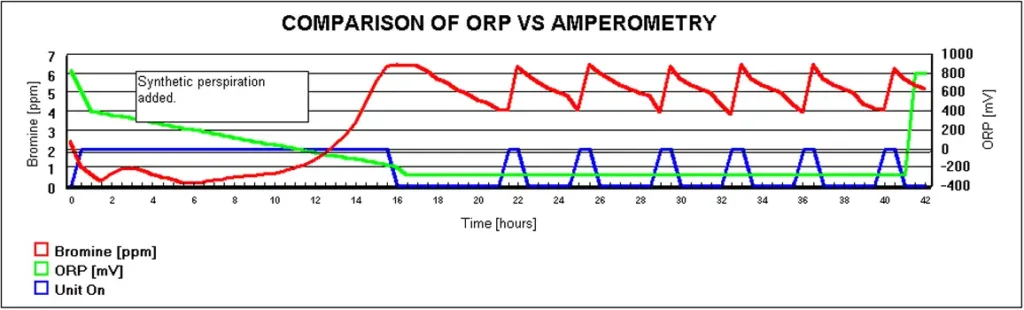

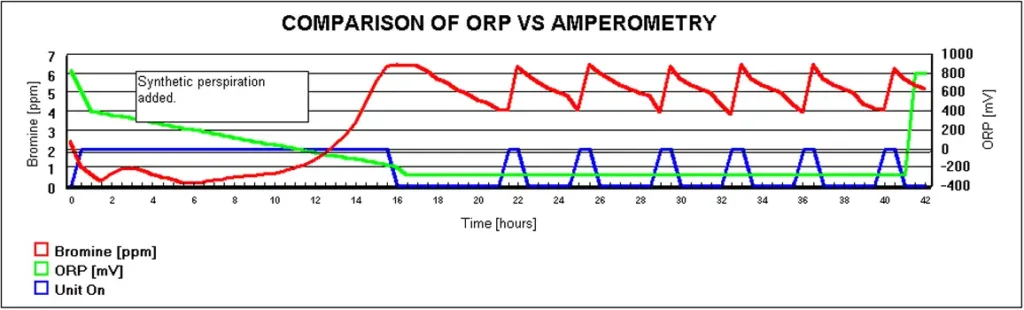

Figure 2 below illustrates the results on an experiment in 300 gallon spa using bromine as the sanitizer. An ORP Sensor was installed as a monitor (not controlling). A bromine generator with an amperometric sensor was also installed to control the sanitizer level. Synthetic perspiration was then added to the spa. The red line is the bromine level that the amperometric system measured throughout the test. The peaks in the blue line represent the time that the bromine generator was energized to satisfy demand. The synthetic perspiration (White, 1992)created a significant demand that persisted throughout the test, requiring the bromine generator to operate for about two hours at a time. After about 12 hours the ORP sensor, represented by the green line, registered negative values. The most likely cause was poisoning of the electrode. It did not recover from the condition for 29 hours. This would have caused a massive over chlorination or over bromination of the spa, had it been controlling the sanitizer.

In this test, synthetic perspiration was added to a hot tub with an electrolytic bromine generation unit. As can be seen above, the green line (ORP) dropped to a negative value before returning to normal after over 29 hours. (Silveri, 1999)

Baseline (zero chlorine) Level Varies with Different Water

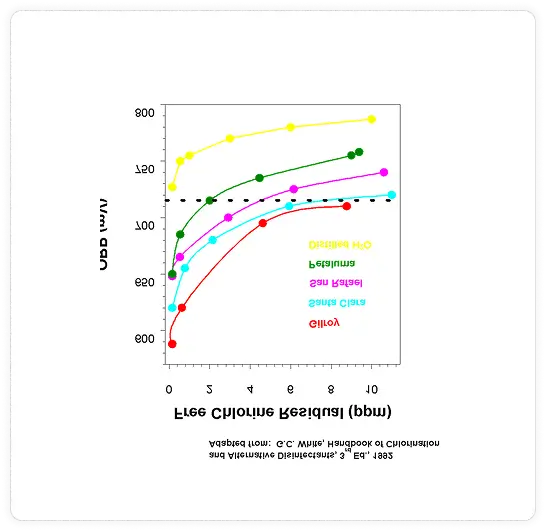

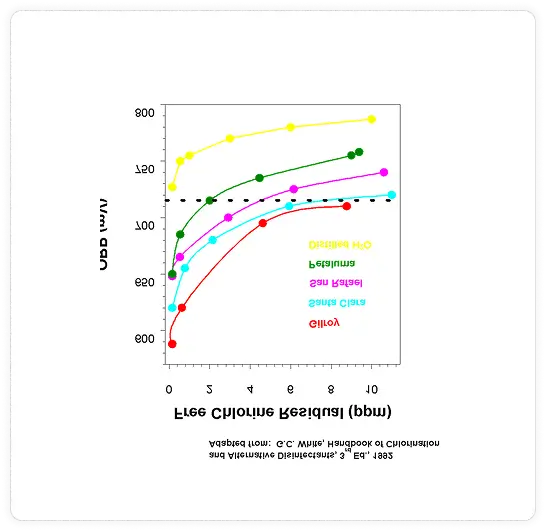

As can be seen from the graph in Figure 3, five different water samples have a different ORP baseline that results in a higher ORP for the same chlorine level. The results vary by almost 200 mV. According to WHO, “there is a wide variation between 720 mV in different waters (1 ppm to 15 ppm chlorine) due to varying baseline ORP (zero chlorine)” (World Health Organization, 2006)

With amperometric sensors, zero current is always zero chlorine, so no zero calibration is needed. It should be noted that this comparison was in tap water. Baseline ORP of seawater ORP can range from -275 to 350 mV greatly exacerbating the baseline problem. (Cohrs, 2004)

The lower oxidation potential of bromine compared to chlorine means that ORP will not be as sensitive to the concentration as it will with chlorine. This also means that the potential from an ORP sensor will be closer to the baseline level (zero bromine level).

CONCENTRATION MEASUREMENT WITH ORP

The limitations of using ORP for chlorine concentration measurement are listed below:

According the Nernst equation that governs the relationship of ORP to the potential measurement, the coefficient that multiplies this logarithm of concentration is equal to -59.16 mV, divided by the number of electrons in the half-reaction (n). In this case, n = 2; therefore, the coefficient is -29.58. A 10-fold change in the concentration of Cl-, HOCl, H+ will only change the ORP ±29.58 mV. (Emerson Process Liquid Division, 2008)

ORP depends upon chloride ion (Cl-) and pH (H+) as much as it does hypochlorous acid (chlorine in water). Any change in the chloride concentration or pH will affect the ORP. Therefore, to measure chlorine accurately, chloride ion and pH must be measured to a high accuracy or carefully controlled to constant values.

To calculate hypochlorous concentration from the measured millivolts, the measured millivolts will appear as the exponent of 10. The typical accuracy of an ORP measurement is ±5 mV. This error alone will result in the calculated hypochlorous acid concentration being off by more than ±30%. Any drift in the reference electrode or the ORP analyzer will only add to this error.

Any change in the ORP with temperature is not compensated, further increasing the error in the derived concentration.

Virtually all ORP half reactions involve more than one substance, and the vast majority have pH dependence. The logarithmic dependence of ORP on concentration multiplies any errors in the measured millivolts.

ORP electrodes are easily poisoned rendering them useless for hours at a time unless they are removed and cleaned.

Use of ORP in seawater electro-chlorination only magnifies most of the inherent problems.

Zero calibration with ORP is difficult since different waters or contaminants with change the baseline. In seawater the baseline can range from -275 to 350 mV.

A logical conclusion from the foregoing is that ORP is not a good technique to apply to concentration measurements.

CONCENTRATION MEASUREMENT WITH ORP

The limitations of using ORP for chlorine concentration measurement are listed below:

According the Nernst equation that governs the relationship of ORP to the potential measurement, the coefficient that multiplies this logarithm of concentration is equal to -59.16 mV, divided by the number of electrons in the half-reaction (n). In this case, n = 2; therefore, the coefficient is -29.58. A 10-fold change in the concentration of Cl-, HOCl, H+ will only change the ORP ±29.58 mV. (Emerson Process Liquid Division, 2008)

ORP depends upon chloride ion (Cl-) and pH (H+) as much as it does hypochlorous acid (chlorine in water). Any change in the chloride concentration or pH will affect the ORP. Therefore, to measure chlorine accurately, chloride ion and pH must be measured to a high accuracy or carefully controlled to constant values.

To calculate hypochlorous concentration from the measured millivolts, the measured millivolts will appear as the exponent of 10. The typical accuracy of an ORP measurement is ±5 mV. This error alone will result in the calculated hypochlorous acid concentration being off by more than ±30%. Any drift in the reference electrode or the ORP analyzer will only add to this error.

Any change in the ORP with temperature is not compensated, further increasing the error in the derived concentration.

Virtually all ORP half reactions involve more than one substance, and the vast majority have pH dependence. The logarithmic dependence of ORP on concentration multiplies any errors in the measured millivolts.

ORP electrodes are easily poisoned rendering them useless for hours at a time unless they are removed and cleaned.

Use of ORP in seawater electro-chlorination only magnifies most of the inherent problems.

Zero calibration with ORP is difficult since different waters or contaminants with change the baseline. In seawater the baseline can range from -275 to 350 mV.

A logical conclusion from the foregoing is that ORP is not a good technique to apply to concentration measurements.

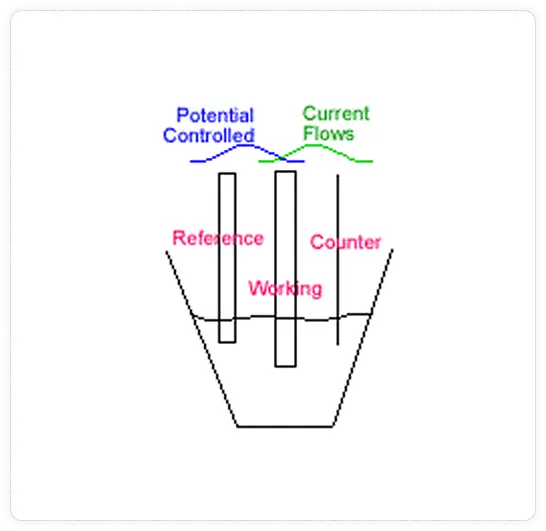

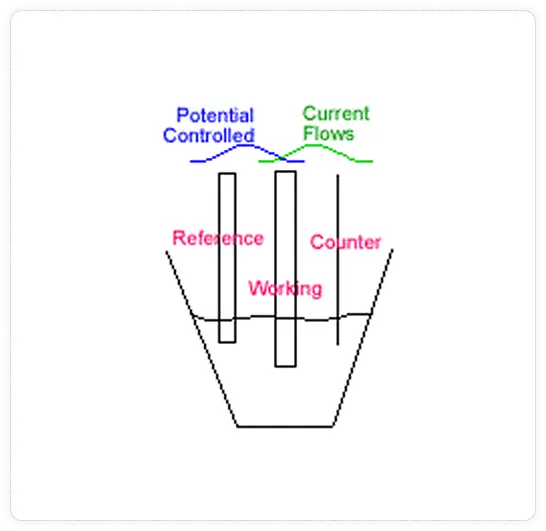

Amperometry

In an amperometric sensor, a fixed voltage is applied between two electrodes and a reaction takes place at the working electrode (cathode) in which chlorine is reduced from chlorine (HOCl) back to chloride (Cl-) Figure 4. This is reverse of what takes place in the chlorine generator where chlorine is generated at the anode. In an amperometric sensor the current that flows as a result of this reduction is proportional to the chlorine presented to the sensor. The figure above shows the “three electrode” configuration. Most membrane chlorine sensors use the “two electrode” method. In general, the two electrode method readings are not as stable and electrodes will not last as long as the three electrode method.

When chlorine is added to water it hydrolyzes to form:

Cl2 + H2O → HOCl + H+ + Cl-

HOCl (aq)OCl- (aq) + H+(aq)

It is usually hypochlorous acid (HOCl) that is measured by the amperometric membrane sensor

LOGARITHMIC VS. LINEAR SIGNAL RELATIONSHIP

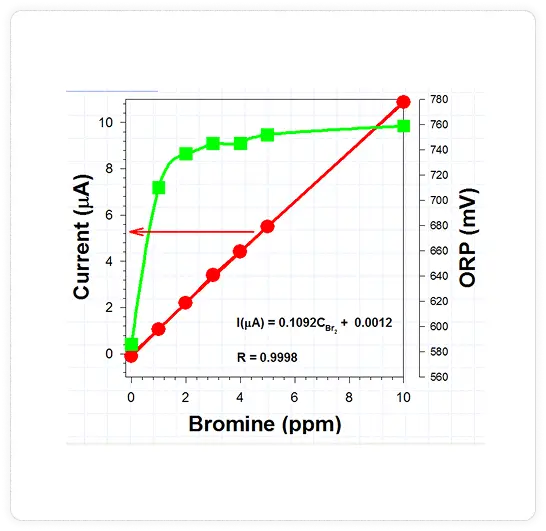

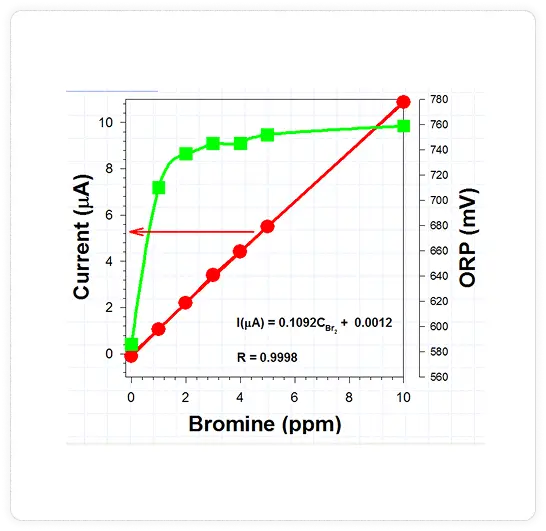

As may be seen from Figure 5, in amperometric systems, the relationship to chlorine (or bromine) is linear vs. the logarithmic relationship for ORP. Any attempt to control bromine at 2 to 4 ppm will not result in very tight control since there is very poor resolution in that range when bromine is the oxidant.

Problems with use of orp in swimming pools

Cyanuric acid is widely used in virtually all outdoor swimming pools to prevent loss of chlorine due to ultraviolet light (sunlight). The most common form of stabilized chlorine is contains over 50% cyanuric acid by weight. As a result, in one season, cyanuric acid levels can increase rapidly, often exceeding 200 ppm. Levels above 300 ppm are often encountered in Arizona, California and Nevada. At levels of around 350 ppm, the ORP electrode is rapidly poisoned and must be cleaned every three days or so. There is no practical way to remove cyanuric acid other than draining some or all of the water. ORP systems cannot be used with high levels of cyanuric acid (over 40 ppm) while Amperometric systems can be used with Cyanuric Acid levels over 200. According to one ORP controller manufacturer swimming pools should not be run with more than 40 ppm of cyanuric acid even though most health departments allow up to 100 ppm and some even allow up to 200 ppm of cyanuric acid. This results in higher costs due to draining a portion of the water. The reason for this recommendation is, according to the company, that ORP increases when the sun goes down as the cyanuric acid. This allows the chlorine level to drop since the controller thinks there is more chlorine than there really is. The next morning when the sun rises the controller detects dangerously low levels of chlorine enters an alarm mode (when a condition of < 200 mV is detected) and shuts down the feed system, detecting a problem that requires intervention. As a result, commercial pools have to spend more money on water, in short supply in many areas, and suffer from needless control problems. HSI’s sensor is the only amperometric sensor that can be used in this application with high levels of cyanuric acid.

problems with orp in wastewater

A report comparing ORP to Amperometric sensors had the following comments regard ORP’s use in wastewater treatment plants:

“Ability to Provide Information to Meet Effluent Coliform Requirements” criterion, a score of two [out of 5] was determined. This score is lower than those given to the residual technologies for this same criterion because of questions raised in Chapter 9.0 that indicate ORP is not always correlated to microbial kill or may not operate successfully in all wastewater applications. Initial evidence suggests that: 1) some chemicals other than chlorine can elevate ORP levels but not produce effective microbial kill, 2) other chemicals can interfere with ORP function, and 3) that ORP may not be an effective solution for all wastewater applications based on the issues raised by points 1) and 2).

The authors point out, however, that some wastewater treatment plants have successfully used ORP and it does play a role in providing qualitative assessments of water quality.

“The ORP technology was given a criteria score of 2 for the criteria “Ability to Provide Process Control System Reliability”. As discussed in Chapter 7.0, there are concerns on how to check if ORP sensors are out of calibration. The inability to effectively predict or determine when an ORP analyzer goes out of calibration can impact process control stability.“

“Based on results from this work it was found that lab ORP probes couldn’t be used effectively to check field ORP calibrations because the lab units are easily fouled or poisoned by wastewater components (See Chapter 7.0).”

“Another concern is that ORP sensors from different manufacturers respond differently to variations in chlorine speciation.” (Damon S. Williams Associates, LLC, 2004)

In summary

In amperometric systems, the relationship to chlorine (or bromine) is linear vs. logarithmic for ORP. ORP will not be precise, require greater training, monitoring and could result in excessive corrosion of components or tanks, often defeating the purpose or its use in the first place.

Amperometric systems actually measures bromine (TRO) not some other parameter (redox), hence will be more accurate.

Zero chlorine is always zero, so no zero calibration is needed with amperometric systems.

Amperometric systems’ electrodes are not easily poisoned by organics as ORP electrodes are.

ORP is both a good qualitative indicator and a poor quantitative method.

ORP Conclusions

The disadvantages of ORP all relate to routine equipment maintenance, calibration, electrode poisoning, presence of multiple redox couples, and very small exchange current that are logarithmically related to the analyte concentration. Or in other words, the assumption of a reversible chemical equilibrium, fast electrode kinetics, and the lack of interfering reactions are essential for chemical interpretations of the ORP potentials. Unfortunately, these conditions rarely, if ever, are met in real world systems (Kissinger, 1996). ORP can be used for qualitative analysis.

Halogen systems’ rapid response ORP

Halogen Systems included ORP measurement in its multi parameter sensor as an indicator for contamination. While the sensor’s chlorine measurement can detect chlorine from .05 to 15 ppm, it cannot detect the difference between contamination and water in which the chlorine residual was recently depleted. ORP can potentially fill in this gap by identifying a contamination event or cross connection by indicating a drop below the baseline ORP level. In addition, HSI’s measurement technique and self-cleaning system actually eliminates poisoning issues, providing a more reliable reading. While HSI’s ORP measurement may have a slight offset from other sensors but provides a reliable, qualitative measurement that overcomes many of the ORP problems.

References

Battelle. (2004)

Long-Term Deployment of Multi-Parameter Water Quality Probes/Sondes. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency.

Cohrs, D. (2004)

The Properties and Composition of Seawater: An "Elemental" Overview. 1st International Symposium of Water Systems in Aquaria and Zoological Parks, (p. 23). Lisbon, Portugal.

Damon S. Williams Associates, LLC. (2004)

ONLINE MONITORING OF WASTEWATER EFFLUENT CHLORINATION USING OXIDATION REDUCTION POTENTIAL (ORP) VS. RESIDUAL CHLORINE MEASUREMENT. Alexandria, VA: Water Environment Research Foundation WERF.

(1991-1992)

“Electrochemical Series” and “Elements in Seawater”. In P. David R. Lide, CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 72nd Edition (pp. 8-17; 14-10). New York: CRC Press.

Emerson Process Liquid Division. (2008, May Unkown)

Fundamentals of ORP Measurement. Retrieved February 28, 2011, from emersonprocess.com: www2.emersonprocess.com/siteadmincenter/.../Liq_ADS_43-014.pdf

Instrument Testing Assocation. (1990)

Residual Chlorine Analyzers for Water and Wastewater Treatment Applications. Henderson, NV : Instrument Testing Assocation.

Instrument Testing Association. (1995)

Total and Free Chlorine Residual Analyzers Online: Maintenance Benchmarking Study. Hendersen, NV: Instrument Testing Association.

International Organization for Standards. (2003)

ISO15839 Water Quality-- On-line Sensors/analysing equipment for water- Specifications and Performance Tests. Geneva, Switzerland: ISO.

ISO International Standards. (2003)

ISO15839 Water quality-- On-line sensors/analysing equipment for water--Specifications and performance tests. Geneva, Switzerland: ISO.

J, M. (2006)

The Chemistry of Gold Extraction, 2nd Edition. Iain House, Published by SME.

Kemmer, F. (1988)

Nalco Water Handbook, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Kissinger, P. (1996)

Laboratory Techniques in Electroanalytical Chemistry2nd Ed. . New York: Marcel Decker.

McPherson, L. (2002, Spring)

Understanding Oxidation Reduction Potential (ORP) Systems. Retrieved from Walchem Corporation.

Panguluri, S. G. (2009)

DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM WATER QUALITY MONITORING: SENSOR TECHNOLOGY EVALUATION METHODOLOGY AND RESULTS. Washington, DC: U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY .

Piela, B. P. (2003)

Electrochemical Behavior of Chloramines on the Rotating Platinum and Gold Electrodes. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, E255- E265.

SAMA Standard PMC 31.1. (1980)

Generic Test Methods for the Testing and Evaluation of Process Measurement and Control Instrumentation. Williamsbury, VA: Measurement Control & Automation Association.

Silveri, M. C. (1999).

On-Line ‘Reagentless’ Amperometric Method for Determination of Bromine in Spas. Proceedings of the 4th Annual Chemistry Symposium National Spa and Pool Institute (pp. 37-43). Las Vegas, NV: National Swimming Pool Institute.

Silveri, M. C. (2001, August 7)

Patent No. 6270680B1. US.

The Measurement, Control and Automation Association, 1980. (1980)

Generic Test Methods for the Testing and Evaluation of Process Measurement and Control Instrumentation. The Measurement, Control and Automation Association.

Wegand, J., Lucas, K., Jackovic, T., & Slebodnick, P. a. (2001)

Submarine Biofouling Control- Chlorination DATS Study at Pearl Harbor", Report number: A565293. Washington DC: Naval Research Lab.

White, G. C. (1992)

The Handbook of Chlorination and Alternative Disinfectants, 3rd Edition. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

World Health Organization. (2006)

Guidelines for Safe Recreation Water Environments. Volume 2. New York, NY: World Health Organization.

Total Residual Oxidant Measurement: ORP or Amperometry

There are two available methods for Total Residual Oxidant (TRO) measurement: Oxidation Reduction Potential (ORP) and amperometry. Until now, there have been no amperometric sensors that have been practical in a ballast water application. This paper will examine the relative benefits and limitations of both methods.

ORP measurement is the least expensive method available for water monitoring. It is primarily used in the swimming pool industry as well as some niche applications such as cyanide destruction (plating and mining industries). It is frequently used as a qualitative indicator. In commercial swimming pools, when used to control chlorine feeding equipment most operators frequently measure the chlorine level manually, often on a daily basis. The presence of high levels of organic molecules can foul the sensor within days, requiring cleaning.

ORP stands for oxidation-reduction potential, which is a measure, in millivolts, of the tendency of a chemical substance to oxidize or reduce another chemical substance. Oxidation is the loss of electrons by an atom, molecule, or ion. The electrons lost by the atom in the reaction cannot exist in solution and have to be accepted by another substance in solution. So the complete reaction involving the oxidation will have to include another substance, which will be reduced Figure 1.

THE MEASUREMENT OF ORP

An ORP sensor consists of an ORP electrode and a reference electrode, as a Voltmeter measures the difference in potential (voltage). The principle behind the ORP measurement is the use of an inert metal electrode (platinum, sometimes gold), which, due to its low resistance, will give up electrons to an oxidant (chlorine in this case) or accept electrons from a reductant (sulfur dioxide in a dechlorination process) . The ORP electrode will continue to accept or give up electrons until it develops a potential, due to the build up charge, which is equal to the ORP of the solution. The typical accuracy of an ORP measurement is ±5 mV. This further complicated by the fact that different probes from the same manufacturer often will have a 20 to 50 mV difference in the same water sample.

An ORP sensor consists of an ORP electrode and a reference electrode, as a Voltmeter measures the difference in potential (voltage). The principle behind the ORP measurement is the use of an inert metal electrode (platinum, sometimes gold), which, due to its low resistance, will give up electrons to an oxidant (chlorine in this case) or accept electrons from a reductant (sulfur dioxide in a dechlorination process) . The ORP electrode will continue to accept or give up electrons until it develops a potential, due to the build up charge, which is equal to the ORP of the solution. The typical accuracy of an ORP measurement is ±5 mV. This further complicated by the fact that different probes from the same manufacturer often will have a 20 to 50 mV difference in the same water sample.

Note: manufactures test their sensors in Zobell Solution which contains a high level of redox couples. In this solution sensors will read very close to each other. That is not the case with real world samples in drinking water.

ORP Electrodes are Easily Poisoned

Figure 2 below illustrates the results on an experiment in 300 gallon spa using bromine as the sanitizer. An ORP Sensor was installed as a monitor (not controlling). A bromine generator with an amperometric sensor was also installed to control the sanitizer level. Synthetic perspiration was then added to the spa. The red line is the bromine level that the amperometric system measured throughout the test. The peaks in the blue line represent the time that the bromine generator was energized to satisfy demand. The synthetic perspiration (White, 1992)created a significant demand that persisted throughout the test, requiring the bromine generator to operate for about two hours at a time. After about 12 hours the ORP sensor, represented by the green line, registered negative values. The most likely cause was poisoning of the electrode. It did not recover from the condition for 29 hours. This would have caused a massive over chlorination or over bromination of the spa, had it been controlling the sanitizer.

In this test, synthetic perspiration was added to a hot tub with an electrolytic bromine generation unit. As can be seen above, the green line (ORP) dropped to a negative value before returning to normal after over 29 hours. (Silveri, 1999)

Baseline (zero chlorine) Level Varies with Different Water

As can be seen from the graph in Figure 3, five different water samples have a different ORP baseline that results in a higher ORP for the same chlorine level. The results vary by almost 200 mV. According to WHO, “there is a wide variation between 720 mV in different waters (1 ppm to 15 ppm chlorine) due to varying baseline ORP (zero chlorine)” (World Health Organization, 2006)

With amperometric sensors, zero current is always zero chlorine, so no zero calibration is needed. It should be noted that this comparison was in tap water. Baseline ORP of seawater ORP can range from -275 to 350 mV greatly exacerbating the baseline problem. (Cohrs, 2004)

The lower oxidation potential of bromine compared to chlorine means that ORP will not be as sensitive to the concentration as it will with chlorine. This also means that the potential from an ORP sensor will be closer to the baseline level (zero bromine level).

CONCENTRATION MEASUREMENT WITH ORP

The limitations of using ORP for chlorine concentration measurement are listed below:

According the Nernst equation that governs the relationship of ORP to the potential measurement, the coefficient that multiplies this logarithm of concentration is equal to -59.16 mV, divided by the number of electrons in the half-reaction (n). In this case, n = 2; therefore, the coefficient is -29.58. A 10-fold change in the concentration of Cl-, HOCl, H+ will only change the ORP ±29.58 mV. (Emerson Process Liquid Division, 2008)

ORP depends upon chloride ion (Cl-) and pH (H+) as much as it does hypochlorous acid (chlorine in water). Any change in the chloride concentration or pH will affect the ORP. Therefore, to measure chlorine accurately, chloride ion and pH must be measured to a high accuracy or carefully controlled to constant values.

To calculate hypochlorous concentration from the measured millivolts, the measured millivolts will appear as the exponent of 10. The typical accuracy of an ORP measurement is ±5 mV. This error alone will result in the calculated hypochlorous acid concentration being off by more than ±30%. Any drift in the reference electrode or the ORP analyzer will only add to this error.

Any change in the ORP with temperature is not compensated, further increasing the error in the derived concentration.

Virtually all ORP half reactions involve more than one substance, and the vast majority have pH dependence. The logarithmic dependence of ORP on concentration multiplies any errors in the measured millivolts.

ORP electrodes are easily poisoned rendering them useless for hours at a time unless they are removed and cleaned.

Use of ORP in seawater electro-chlorination only magnifies most of the inherent problems.

Zero calibration with ORP is difficult since different waters or contaminants with change the baseline. In seawater the baseline can range from -275 to 350 mV.

A logical conclusion from the foregoing is that ORP is not a good technique to apply to concentration measurements.

CONCENTRATION MEASUREMENT WITH ORP

The limitations of using ORP for chlorine concentration measurement are listed below:

According the Nernst equation that governs the relationship of ORP to the potential measurement, the coefficient that multiplies this logarithm of concentration is equal to -59.16 mV, divided by the number of electrons in the half-reaction (n). In this case, n = 2; therefore, the coefficient is -29.58. A 10-fold change in the concentration of Cl-, HOCl, H+ will only change the ORP ±29.58 mV. (Emerson Process Liquid Division, 2008)

ORP depends upon chloride ion (Cl-) and pH (H+) as much as it does hypochlorous acid (chlorine in water). Any change in the chloride concentration or pH will affect the ORP. Therefore, to measure chlorine accurately, chloride ion and pH must be measured to a high accuracy or carefully controlled to constant values.

To calculate hypochlorous concentration from the measured millivolts, the measured millivolts will appear as the exponent of 10. The typical accuracy of an ORP measurement is ±5 mV. This error alone will result in the calculated hypochlorous acid concentration being off by more than ±30%. Any drift in the reference electrode or the ORP analyzer will only add to this error.

Any change in the ORP with temperature is not compensated, further increasing the error in the derived concentration.

Virtually all ORP half reactions involve more than one substance, and the vast majority have pH dependence. The logarithmic dependence of ORP on concentration multiplies any errors in the measured millivolts.

ORP electrodes are easily poisoned rendering them useless for hours at a time unless they are removed and cleaned.

Use of ORP in seawater electro-chlorination only magnifies most of the inherent problems.

Zero calibration with ORP is difficult since different waters or contaminants with change the baseline. In seawater the baseline can range from -275 to 350 mV.

A logical conclusion from the foregoing is that ORP is not a good technique to apply to concentration measurements.

Amperometry

In an amperometric sensor, a fixed voltage is applied between two electrodes and a reaction takes place at the working electrode (cathode) in which chlorine is reduced from chlorine (HOCl) back to chloride (Cl-) Figure 4. This is reverse of what takes place in the chlorine generator where chlorine is generated at the anode. In an amperometric sensor the current that flows as a result of this reduction is proportional to the chlorine presented to the sensor. The figure above shows the “three electrode” configuration. Most membrane chlorine sensors use the “two electrode” method. In general, the two electrode method readings are not as stable and electrodes will not last as long as the three electrode method.

When chlorine is added to water it hydrolyzes to form:

Cl2 + H2O → HOCl + H+ + Cl-

HOCl (aq)OCl- (aq) + H+(aq)

It is usually hypochlorous acid (HOCl) that is measured by the amperometric membrane sensor

LOGARITHMIC VS. LINEAR SIGNAL RELATIONSHIP

As may be seen from Figure 5, in amperometric systems, the relationship to chlorine (or bromine) is linear vs. the logarithmic relationship for ORP. Any attempt to control bromine at 2 to 4 ppm will not result in very tight control since there is very poor resolution in that range when bromine is the oxidant.

Problems with use of orp in swimming pools

Cyanuric acid is widely used in virtually all outdoor swimming pools to prevent loss of chlorine due to ultraviolet light (sunlight). The most common form of stabilized chlorine is contains over 50% cyanuric acid by weight. As a result, in one season, cyanuric acid levels can increase rapidly, often exceeding 200 ppm. Levels above 300 ppm are often encountered in Arizona, California and Nevada. At levels of around 350 ppm, the ORP electrode is rapidly poisoned and must be cleaned every three days or so. There is no practical way to remove cyanuric acid other than draining some or all of the water. ORP systems cannot be used with high levels of cyanuric acid (over 40 ppm) while Amperometric systems can be used with Cyanuric Acid levels over 200. According to one ORP controller manufacturer swimming pools should not be run with more than 40 ppm of cyanuric acid even though most health departments allow up to 100 ppm and some even allow up to 200 ppm of cyanuric acid. This results in higher costs due to draining a portion of the water. The reason for this recommendation is, according to the company, that ORP increases when the sun goes down as the cyanuric acid. This allows the chlorine level to drop since the controller thinks there is more chlorine than there really is. The next morning when the sun rises the controller detects dangerously low levels of chlorine enters an alarm mode (when a condition of < 200 mV is detected) and shuts down the feed system, detecting a problem that requires intervention. As a result, commercial pools have to spend more money on water, in short supply in many areas, and suffer from needless control problems. HSI’s sensor is the only amperometric sensor that can be used in this application with high levels of cyanuric acid.

problems with orp in wastewater

A report comparing ORP to Amperometric sensors had the following comments regard ORP’s use in wastewater treatment plants:

“Ability to Provide Information to Meet Effluent Coliform Requirements” criterion, a score of two [out of 5] was determined. This score is lower than those given to the residual technologies for this same criterion because of questions raised in Chapter 9.0 that indicate ORP is not always correlated to microbial kill or may not operate successfully in all wastewater applications. Initial evidence suggests that: 1) some chemicals other than chlorine can elevate ORP levels but not produce effective microbial kill, 2) other chemicals can interfere with ORP function, and 3) that ORP may not be an effective solution for all wastewater applications based on the issues raised by points 1) and 2).

The authors point out, however, that some wastewater treatment plants have successfully used ORP and it does play a role in providing qualitative assessments of water quality.

“The ORP technology was given a criteria score of 2 for the criteria “Ability to Provide Process Control System Reliability”. As discussed in Chapter 7.0, there are concerns on how to check if ORP sensors are out of calibration. The inability to effectively predict or determine when an ORP analyzer goes out of calibration can impact process control stability.“

“Based on results from this work it was found that lab ORP probes couldn’t be used effectively to check field ORP calibrations because the lab units are easily fouled or poisoned by wastewater components (See Chapter 7.0).”

“Another concern is that ORP sensors from different manufacturers respond differently to variations in chlorine speciation.” (Damon S. Williams Associates, LLC, 2004)

In summary

In amperometric systems, the relationship to chlorine (or bromine) is linear vs. logarithmic for ORP. ORP will not be precise, require greater training, monitoring and could result in excessive corrosion of components or tanks, often defeating the purpose or its use in the first place.

Amperometric systems actually measures bromine (TRO) not some other parameter (redox), hence will be more accurate.

Zero chlorine is always zero, so no zero calibration is needed with amperometric systems.

Amperometric systems’ electrodes are not easily poisoned by organics as ORP electrodes are.

ORP is both a good qualitative indicator and a poor quantitative method.

ORP Conclusions

The disadvantages of ORP all relate to routine equipment maintenance, calibration, electrode poisoning, presence of multiple redox couples, and very small exchange current that are logarithmically related to the analyte concentration. Or in other words, the assumption of a reversible chemical equilibrium, fast electrode kinetics, and the lack of interfering reactions are essential for chemical interpretations of the ORP potentials. Unfortunately, these conditions rarely, if ever, are met in real world systems (Kissinger, 1996). ORP can be used for qualitative analysis.

Halogen systems’ rapid response ORP

Halogen Systems included ORP measurement in its multi parameter sensor as an indicator for contamination. While the sensor’s chlorine measurement can detect chlorine from .05 to 15 ppm, it cannot detect the difference between contamination and water in which the chlorine residual was recently depleted. ORP can potentially fill in this gap by identifying a contamination event or cross connection by indicating a drop below the baseline ORP level. In addition, HSI’s measurement technique and self-cleaning system actually eliminates poisoning issues, providing a more reliable reading. While HSI’s ORP measurement may have a slight offset from other sensors but provides a reliable, qualitative measurement that overcomes many of the ORP problems.

References

Battelle. (2004)

Long-Term Deployment of Multi-Parameter Water Quality Probes/Sondes. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency.

Cohrs, D. (2004)

The Properties and Composition of Seawater: An "Elemental" Overview. 1st International Symposium of Water Systems in Aquaria and Zoological Parks, (p. 23). Lisbon, Portugal.

Damon S. Williams Associates, LLC. (2004)

ONLINE MONITORING OF WASTEWATER EFFLUENT CHLORINATION USING OXIDATION REDUCTION POTENTIAL (ORP) VS. RESIDUAL CHLORINE MEASUREMENT. Alexandria, VA: Water Environment Research Foundation WERF.

(1991-1992)

“Electrochemical Series” and “Elements in Seawater”. In P. David R. Lide, CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 72nd Edition (pp. 8-17; 14-10). New York: CRC Press.

Emerson Process Liquid Division. (2008, May Unkown)

Fundamentals of ORP Measurement. Retrieved February 28, 2011, from emersonprocess.com: www2.emersonprocess.com/siteadmincenter/.../Liq_ADS_43-014.pdf

Instrument Testing Assocation. (1990)

Residual Chlorine Analyzers for Water and Wastewater Treatment Applications. Henderson, NV : Instrument Testing Assocation.

Instrument Testing Association. (1995)

Total and Free Chlorine Residual Analyzers Online: Maintenance Benchmarking Study. Hendersen, NV: Instrument Testing Association.

International Organization for Standards. (2003)

ISO15839 Water Quality-- On-line Sensors/analysing equipment for water- Specifications and Performance Tests. Geneva, Switzerland: ISO.

ISO International Standards. (2003)

ISO15839 Water quality-- On-line sensors/analysing equipment for water--Specifications and performance tests. Geneva, Switzerland: ISO.

J, M. (2006)

The Chemistry of Gold Extraction, 2nd Edition. Iain House, Published by SME.

Kemmer, F. (1988)

Nalco Water Handbook, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Kissinger, P. (1996)

Laboratory Techniques in Electroanalytical Chemistry2nd Ed. . New York: Marcel Decker.

McPherson, L. (2002, Spring)

Understanding Oxidation Reduction Potential (ORP) Systems. Retrieved from Walchem Corporation.

Panguluri, S. G. (2009)

DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM WATER QUALITY MONITORING: SENSOR TECHNOLOGY EVALUATION METHODOLOGY AND RESULTS. Washington, DC: U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY .

Piela, B. P. (2003)

Electrochemical Behavior of Chloramines on the Rotating Platinum and Gold Electrodes. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, E255- E265.

SAMA Standard PMC 31.1. (1980)

Generic Test Methods for the Testing and Evaluation of Process Measurement and Control Instrumentation. Williamsbury, VA: Measurement Control & Automation Association.

Silveri, M. C. (1999).

On-Line ‘Reagentless’ Amperometric Method for Determination of Bromine in Spas. Proceedings of the 4th Annual Chemistry Symposium National Spa and Pool Institute (pp. 37-43). Las Vegas, NV: National Swimming Pool Institute.

Silveri, M. C. (2001, August 7)

Patent No. 6270680B1. US.

The Measurement, Control and Automation Association, 1980. (1980)

Generic Test Methods for the Testing and Evaluation of Process Measurement and Control Instrumentation. The Measurement, Control and Automation Association.

Wegand, J., Lucas, K., Jackovic, T., & Slebodnick, P. a. (2001)

Submarine Biofouling Control- Chlorination DATS Study at Pearl Harbor", Report number: A565293. Washington DC: Naval Research Lab.

White, G. C. (1992)

The Handbook of Chlorination and Alternative Disinfectants, 3rd Edition. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

World Health Organization. (2006)

Guidelines for Safe Recreation Water Environments. Volume 2. New York, NY: World Health Organization.